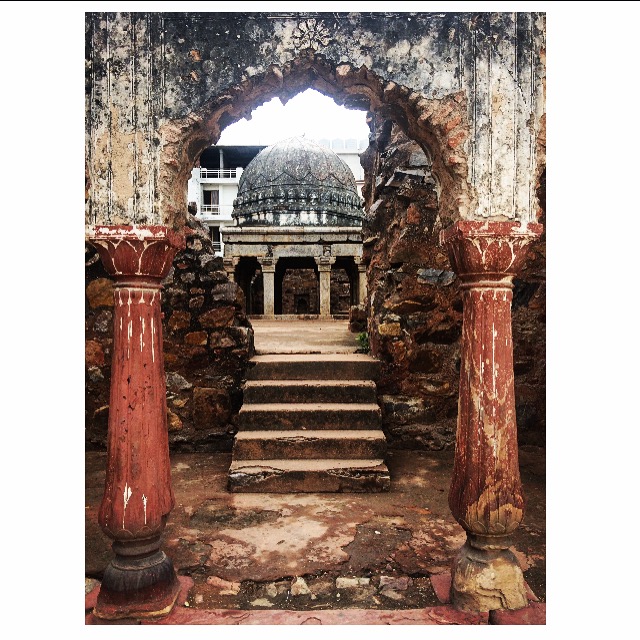

Farrukhnagar is a town 25 kilometers away from the city of Gurgaon, once one of the most important city for salt trade now lies in ruins with its dilapidated Monuments.

Established in 1732 by Faujdar Khan, the first Nawab of Farrukhnagar and a governor of Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar in 1732, Farrukhnagar flourished due to its salt trade till the late 19th century and was abandoned in the early 20th century, during the British Raj. Sultanpur was the center of salt production for use in Delhi and provinces of Oudh and Agra. till the late 19th century exporting annually 680,000 maunds or 18,350 tons over the Rajputana-Malwa Railway. Salt was produced by extracting brine from about 40 wells using bullocks and drying in open plots. Since salt was one of the major sources of government’s revenue, the office of the Salt Superintendent at Sultanpur supervised the levy of Rs.2 per maund. With the levy of the heavy salt tax by the government, the Sultanpur salt became uneconomical and by 1903-04 the salt industry was struggling for survival with salt export having fallen to 65,000 maunds or 1,750 tons leading to the severe setback to the economy of Sultanpur area. Finally, in 1923 the British shut down the office of the salt superintendent at Sultanpur had all the mounds of salt thrown back into the wells and shut down the salt industry leading to considerable economic misery to the people.

Farrukhnagar houses numerous monuments which needed serious government attention.

Few monuments which I came across during my visit were

I couldn’t go inside the monument because it was closed on Sunday

No one knows when this Mosque was converted, but as per assumption after Nawab Ahmed Ali Khan of Farukhnagar was executed for the uprising of 1857 against Britishers the mosque came in the hands of Hindu authorities.

Btw this confusing structure also has a board which says it is also a Gurudwara.

I was not able to capture any good images because the gates of the Mandir were closed and clicking the picture of this monument was too suspicious for the localites.

Getting there & around

The driving time from Delhi to Farukhnagar is up to two hours, depending on traffic. Private taxis charge approximately Rs 2,000 for a round trip from Gurgaon. Regular bus services are available from the Gurgaon bus stand in Sector 14, and tickets cost Rs 18-20. Using your own car or hiring a taxi is most convenient as the only means of transport within Farrukhnagar are communal autorickshaws that ply on fixed routes.

s tomb and a big Chhatri. The complex site has superimposed structures which indicate the continuous additions of structures at the same place

s tomb and a big Chhatri. The complex site has superimposed structures which indicate the continuous additions of structures at the same place

According to the British civil servant Lewis O’Malley, writing in 1911, “the name Dum Dum is a corruption of Damdama, meaning a raised mound or battery. It appears to have first applied to an old house standing on a raised mound”. The house is non another than the “Clive House”

According to the British civil servant Lewis O’Malley, writing in 1911, “the name Dum Dum is a corruption of Damdama, meaning a raised mound or battery. It appears to have first applied to an old house standing on a raised mound”. The house is non another than the “Clive House”

The history of Bansberia dates back to the days of Shah Jahan. In 1656, the Mughal emperor appointed Raghab Dattaroy of Patuli as the zamindar of an area that includes the present-day Bansberia. Legend has it that Raghab’s son Rameshwar cleared a bamboo grove to build a fort, inspiring the name Bansberia.

The history of Bansberia dates back to the days of Shah Jahan. In 1656, the Mughal emperor appointed Raghab Dattaroy of Patuli as the zamindar of an area that includes the present-day Bansberia. Legend has it that Raghab’s son Rameshwar cleared a bamboo grove to build a fort, inspiring the name Bansberia.